The Church of Orsanmichele was in the thick of it. It was, and still is, on the main street that leads from Florence’s cathedral to the main plaza. So when Florence’s governors decreed that Orsanmichele’s outside niches be filled with sculptures, everyone would see these art works on a daily basis.

They were destined to become some of the West’s most influential art works. Most were fashioned at the beginning of the 15th century, and they influenced all the great painting and sculpture that came from Florence throughout the Renaissance. A closer look at them not only takes you into key roots of Western civ–it’s a great point of comparison with other cultures. Yeah, the guy in the photo looks heavy and intense, if you look closely, you can fly higher than the dome on Florence’s cathedral.

Florence had conquered Pisa in 1406, and its political leaders wanted to push the Orsanmichele sculptural project to completion within the decade to glorify their city. Each major trade guild was told to finance a carving of its patron saint, which would fill one of the niches.

Different artists took on the projects. Lorenzo Ghiberti was one of the 2 most influential. He crafted the huge bronze statue of St. John the Baptist in the above photo. It’s largely Gothic in style–there’s no hint of a body beneath the drapery folds, and the face and hair are more abstract than individual. But it’s massive and monumental. Its blending of Gothic and ancient Roman styles begins to point to a new world.

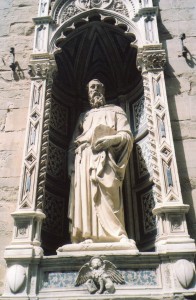

Donatello, the other great sculptor, made St. Mark (above) in marble. His figure looks more real. His face looks more like a real person’s, and his drapery is different over each leg. His right leg is still, and the gown hangs straight down. But the clothing is looser over the other leg, which is more relaxed and flexed. Donatello suggests real flesh and a personality.

Meanwhile, another sculptor, Nanni di Banco, was working on another expression of the body in the material world. The 4 men in the above niche were Christian sculptors in ancient Rome, who refused to carve an image of a pagan god for the emperor Diocletian. They were martyred around 300 CE. Three things stand out about them:

1. They have the dignity and massiveness of Roman emperors and senators

2. They relate to each other as men–nobody’s looking up to his maker, or meditating to find divinity within. The locus of reality is face to face.

3. They comprise a three-dimensional space.

So Florence’s artists and merchants were taking their city from Gothic style, which stresses the general and spiritual, and into the material world. This new world stresses the body, the community of people and three-dimensional space.

Florentine painters, beginning with Masaccio, followed these sculptors and represented the body’s massiveness and its existence in three-dimensional space. This became as important as the emphasis on abstract lines in Western culture. Both meshed throughout the Renaissance. Modern Westerners have assumed that this mixture is the basis of reality. Its cultural origins are infinitely rich, so we’ll examine them more. But in a cool way–by comparing them with another culture, Southeast Asia. Get ready to fly high.

Comments on this entry are closed.