I got a bit distracted since I wrote the last post on the Bayon, but a little country called China can do that to you. Back to the Bayon, one of the world’s greatest religious monuments.

King Jayavarman VII began it about 50 years after Angkor Wat was built–when Europeans were erecting Chartres Cathedral. Scholars have seen Angkor Wat and the Bayon as Khmer models of the universe. But the Bayon took steps towards a revolution in perspective.

It includes the rest of us. Angkor Wat’s sculpture focuses on gods and the king, and Angkor Wat’s style is formal. But after you walk through the Bayon’s outer enclosure of galleries (the Bayon Part One), you come to the main part of the temple. Its outer walls contain sculpted scenes that give you a panorama of earth and heaven.

Like Angkor Wat, the Bayon has its share of soldiers–Khmers still loved their action scenes. These images include a sea battle which might have represented troops driving the invading Cham soldiers from southern Vietnam out of Angkor–other interpretations have been proposed though.

But the clashing armies are mixed with daily life. Women in their homes prepare meals, Men haul goods on ox carts. A couple, with a child riding on the man’s shoulders, walk behind a cart. Baby goats trot behind its wheels. Men fish with nets, and women sell the lake’s bounty in a market. A crowd watches a cockfight. The perspective of the king, his armies and the gods has expanded to the rest of us.

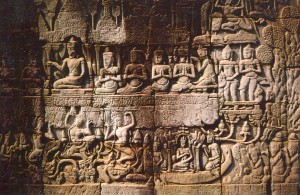

An inner enclosure also contains friezes. There was a Hindu reaction in the late 13th century, under Jayavarman VIII, and many of the scenes have Hindu themes. Vishnu is honored in the above photo.

And Shiva graces the above shot. The temple that he sits in seems to float on a pond of lotuses. Three women dance on flowers directly under him, and on each side of them a boat carries an elegant court lady.

So the Bayon has many types of scenes–earthly and heavenly, domestic and martial. But its sculptures’ style is distinctive–it’s called the Bayon style. Angkor Wat fans say that it’s quality is lower than their favorite temple’s. They Bayon style isn’t as refined, but it’s folksier. The figures seem more approachable. The Mahayana Buddhism which Jayavarman VII embraced emphasized compassion. Was the great king extending it to the common people in his realm?

If so, Jayavarman’s expansion of perspective went only so far. The reliefs still express centralized power. The people aren’t differentiated from the temple and its grandiose scale and stern symmetry–their presence expresses the power of the Buddha and the king. The historian David Chandler wrote that people in Jayvarman’s time were seen as figures of his authority. These carvings aren’t portraits by Titian or Rembrandt that meet your gaze with dignity as individuals. They’re cogs in an enormous cosmic scheme in which centralized power is far more important.

Jayavarman VII might have been looking both forwards and backwards when he built the Bayon. The temple expresses both openness to new perspectives and desires to assert centralized power as ardently as ever after the political instability preceding Jayavarman’s reign, and after the Cham wars.

I felt conflicting emotions while exploring Jayavarman’s world. It was both down-to-earth and heavy-handed. Maybe Khmers had mixed feelings then too–optimism about the new order, but also insecurity about it. It felt liberating to ascend the stairs towards the Bayon’s central section. But only for a few minutes. I was approaching the center of the Khmer universe during the apex of its power, and I wasn’t sure whether I was going to be energized or blown to bits.

Come into the center of the Bayon, if you dare.

Comments on this entry are closed.