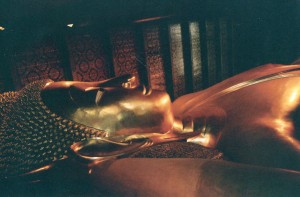

People admire Michelangelo’s David for its size and grace, but it’s got nothing on Wat Pho’s Sleeping Buddha statue.

But the Wat Pho statue was made according to Thai thought patterns, rather than Western.

Michelangelo’s David is big, but the Sleeping Buddha is huge–150 feet long and 50 feet high. I’m looking way up at him in the above shot. He’s lying on his side, and this is one of the 4 traditional positions in Thai Buddha sculptures–sitting, standing, and walking are the others. When he was about to pass away, he calmly reclined on his side and told his followers to look to their own salvations. Thais are usually uncomfortable discussing death (see why in Thai happiness), so they call this posture the sleeping, or reclining Buddha.

Thais made Wat Pho’s Sleeping Buddha with brick, encased it in plaster, and gilded it. Even though it’s gargantuan, I found it one of the smoothest things on earth. It doesn’t have the detailed muscles of Michelangelo’s David. Instead, its lines delicately curve, and the gold leaf that covers it makes it appear as soft as silk. So big, yet otherworldly.

The statue’s form seems to ripple like a river, like the Sukhothai Buddha’s. Rivers are prominent features of traditional Thai life–people usually preferred to establish villages and towns by them and use them for transportation. So a gentle river can symbolize well-being more than the static geometric forms that the West emphasizes do. Thais fused this idea with the Buddhist art that they created. Wat Pho’s Sleeping Buddha was made in the early 19th century–they were well experienced with this form by then, so they could make this enormous statue seem to float in the clouds.

But we have yet to see Wat Pho’s Sleeping Buddha’s most graceful feature. The next post, on the Buddha’s footprint, will explore it.

Comments on this entry are closed.