Suryavarman II, the builder of Angkor Wat, made a walloping Linkedin profile.

Here is one of his key ministers on his mighty elephant, surrounded by parasols. Regal, but I found that Angkor Wat’s style generates mixed feelings.

His features are both elegant and angular, and I found this combo haunting. I think it’s because I felt two emotions at the same time. He’s regal and beautiful, and thus a key source of well-being in the Khmer universe. But he’s also animated and dangerous looking–don’t mess with him. He looks as though he can bestow grace on a whole city or pulverize it by blinking an eye.

Suryavarman II, the Khmer king, probably wanted to convey this message. This portrait looks more idealized than realistic–how many royal ministers have a bod like that? But the Angkor Wat style isn’t known for being down-to-earth.

Sometimes Angkor Wat’s elevated style is utterly spellbinding. I’ll admit to spending more time admiring its roughly 2,000 apsaras (female dancers for the gods) than any other figures.

And Angkor Wat’s celestial elegance flows all the way to the ground. Even the bottom plinth of a library has refined figures and animated foliage. The ornate forms over minute spaces in such a gargantuan monument seemed unreal–that was probably the point, since Angkor Wat is supposed to be a home for gods.

True to form, these figures from the Ramayana are surrounded by florid stencils that are so profuse that they steal the show. But Angkor Wat’s refined style often explodes into gripping violence.

Every square foot of the frieze of the Ramayana’s final battle seems to exude enough power to knock a guy who comes too close on his backside. What gives? Why portray intense battle scenes in a monument with so many delicate female beauties?

One answer might come from the Hindu mythology that the scenes portray. The universe emanates and then dissolves in many cycles. The violence could represent the destruction before the universe begins again. But the Ramayana took place at an earlier phase of cosmic history than our age, so this explanation isn’t logically consistent. I think the natural scenery provides a clue.

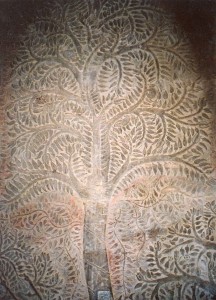

Trees enliven the backgrounds of many of Angkor Wat’s scenes, as they do in Southeast Asian villages and towns today. This tree looks as animated as Suryavarman’s minister is in the first shot–it sure doesn’t remind me of the gently rolling hills in northern California, or the English countryside. It’s infused with nature’s power. It embodies the force in the sun, the monsoons and the jungle that surrounds villages–the natural environment that the Khmers lived in. The king probably portrayed himself as a key director of this power. He, his ministers and the gods could tame it into elegant forms like the library plinth and the stencils, or use it to vanquish enemies.

The carvings on Angkor Wat thus have different personalities–they’re sometimes elegant, and sometimes terrible, but they reflect the power and aristocratic refinement of Suryavarman II, his court, and the gods. Few are ordinary. Angkor Wat sparkles from ground to crown. Some of it can lift you into paradise, and other parts can crush you. You’re in God’s mansion.

But sometimes I found Angkor Wat oppressive. Thai art is full of common touches that reflect the Buddha’s compassion. Banteay Srei is a Khmer temple that’s as beautiful as Angkor Wat, but it’s on a scale that ordinary people can relate to. But Angkor Wat’s hieratic style does its job–prepare to be awed if you go there.

You can see more on the Angkor Wat style in the way that common people were portrayed.

Comments on this entry are closed.