On the surface, the Vedic sky god Indra resembled Zeus. Both lived in a palace in the sky, threw thunderbolts around, and enjoyed their status as the most prestigious god.

But from India’s earliest text, the Rg Veda, Indra had characteristics that suggest that ancient Indians thought in different ways than ancient Greeks did.

The last post took a brief look at Greece’s Homer–at the Iliad’s life-like portrayal of gods. It details their relationships with each other in vivid details. But in the Rg Veda, gods don’t interact nearly as much, and they’re not described in as much detail. Instead it focuses on their cosmic energies.

Indra and Varuna join forces to slay Vrtra and restore the rains. But the Rg Veda doesn’t give long descriptions of their conversations. Homeric texts probably would have added a protracted dialog in which they plot the strategy. They then would have argued over who gets the glory and the war booty. Loving details of their shining armor, limber chariots and furious steeds, whose neighs thunder like the coming monsoon, would have followed.

But the Rg Veda’s focus isn’t on description or narration. It’s on the sacrifices’ efficacy–on making them work. In Ludwig Wittgenstein’s terms, it plays a different language game. It links the power of the gods to the community’s welfare, not by reveling in their visual details, but by channeling their metaphysical power.

Sacred language doesn’t describe as much as it effects–the word Sanskrit means well done.

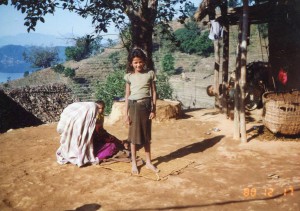

The Rg Veda thus sings of the gods coming down to the ssacred grass to consume people’s gifts to them, and of the god Agni burning and transporting offering to the sky for the gods to enjoy. It doesn’t linger on details in front of your eyes, or on relationships between the gods. Its horizons are less hemmed in by the limits of interpersonal encounters and physical details, and more open to imaginative flights. Ancient Indians believed that focusing on cosmic energies is the best way to ensure well-being–and the lovely smile of the daughter of Indra pictured above.

India often continued to emphasize the vast and cosmic over the individual and physical–the posts on origins of Indian thought show some of the reasons why.

Though both ancient Indians and ancient Greeks made ideas of the storm-brewing sky god central, they both shaped their concepts of him in diffferent ways. These ways reflect both cultures’ basic assumptions about reality. As the post on the theme of return in Homer show, ideas and images take on different traits in different cultures, and they reflect their infinitely rich environments. You can see unlimited wonders in a culture’s most basic ideas.

Comments on this entry are closed.