The Natabeans turned Petra into one of the greatest sites in the ancient world. Let’s find out how.

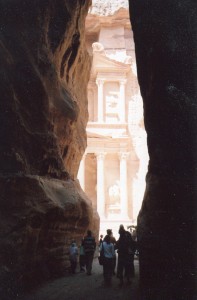

You enter Petra through a cleft between rock that’s about a third of a mile long, and in some places, wide enough for only one chariot. The way into Petra thus made it clear that it’s a special place.

This cleft is called the Siq. It was vulnerable to flash floods until the Nabateans built waterways into the rock to manage the flow. As former desert nomads who were experts at finding hidden waterholes in the desert, they had a long heritage of water management.

As you approach the other end of the Siq, the Treasury gradually comes into view. Its clear and bright forms contrast dramatically with the narrow passageway between the rocks. You’re coming into a divine place. Did people think of the passageway into their city as a birth canal into a place of divine order?

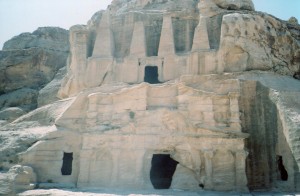

Turn right and more wonders await. You pass lots of tombs that families cut into the rock. Then you come to an amphitheater. Many tombs are visible from its seats. Some specialists thus think that it might have been used for religious rituals.

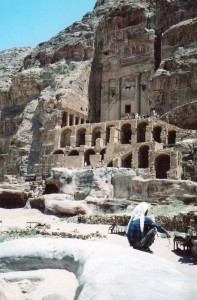

You pass many more rock-cut tombs, and then come to a row of magnificent tombs cut into the cliff on your right. Many specialists think kings were laid to rest there.

These tombs formed one end of Petra’s civic center. The imagination runs wild here.

As the Nabateans grew rich, Petra became one of the world’s greatest emporiums. The civic center blended forms from many cultures. It had a Roman style garden, a royal palace, several temples, and 3 large markets–Nabateans always loved trade.

But Nabateans added their own spirit to these forms. They were more egalitarian than most ancient people. They abhorred slavery and allowed women prominent roles. There’s a small theater with room for about 600 people in a huge colonnaded compound in the middle of town, and it might have been used as an assembly. Some scholars think it was used for religious rituals. But it’s right next to three markets, so maybe people used it for both secular and sacred activities without distinguishing them as sharply as most moderns do.

The royal palace is just across the road. It’s amazingly small for a Middle Eastern royal pad–the residential part is the size of an upper middle class home.

The Greek historian Strabo wrote that Nabateans didn’t quarrel with each other. But foreigners often pressed lawsuits.

At the end of the main street is a large temple for Dushara. Dushara was originally a sky god associated with mountains, storms and rain, like Zeus. Nabatean religion and art originally focused on basic forces of nature (Part Two). They were now building large stone temples for them, and their art was undergoing a big transformation.

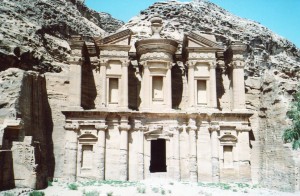

The Nabateans received influences from multiple cultures at the same time. They blended all their forms into mixtures you’ll never forget.

Pictured above is The Monastery, which presides on one of the cliffs over the town. It’s actually a cella with a cultic podium in the back. It’s huge. The doorway is about 8 feet above the ground.

Above is a tomb with Egyptian influences. Petra’s richest families were going to the afterlife in style.

What made Petra so special for me was the mixture of Greco-Roman, Egyptian, Babylonian and Persian cultures in a natural setting that blended intimate politics, the ancestors, the gods, and business. All domains were together. The road in the center of town was surrounded by hundreds of rock-cut tombs that must have been painted brightly in their day. Overhead, cliffs sheltered other tombs and outdoor places of worship.

The Nabateans were proto-Arabs. They left short inscriptions that are ancestors of Arabic. When Arabs embraced Islam and inherited Greco-Roman, Persian and Egyptian civilizations, some of their aesthetics went through a similar process of changing from simplicity to luxurious mixtures of many cultures’ forms. Nabateans were there first, and their later art, with its flowing plant motifs and international blends might have influenced Byzantine and Coptic motifs, which Muslims later inherited.

But people at Petra have kept some of the old simplicity. As I hiked in the hills above town, a man on a camel offered a ride for a fee. I patted his camel’s hump, pointed to my stomach swelling with Middle Eastern pastries, and said, “This is just as good. You pay me, I’ll carry you!”

He called my bluff, “You carry me, I’ll give you the camel!” Direct, quick, confident and always looking for a deal–just like the ancient Nabateans.

You can also go to Facts and Maybes about Petra, Part One, and

Facts and Maybes about Petra, Part Two.

Comments on this entry are closed.