Angkor Wat awes, but Banteay Srei wins hearts. Many visitors to Angkor say that Banteay Srei is their favorite Khmer temple. It might bring out your inner child.

Banteay Srei was built late in the reign of Rajendravarman II, by one of his officials. Rajendravarman had been extending the Khmer Empire, and he punctuated his authority with a grand temple called Pre Rup. Now that the Khmer Empire had a strong backbone, its kings and officials could experiment with new ideas and art forms. One of Angkor’s most creative periods followed.

The builders of Banteay Srei achieved new levels of realism and elegance. Here are some of the things that make it special:

1. Banteay Srei wasn’t built by a king, but by a man called Yajnavaraha. He became the guru of the next monarch, Jayavarman V, whose reign is known for religious tolerance, and for importing many Buddhist ideas. So, Banteay Srei wasn’t built by a chest thumping monarch, but an official who was religious, and it was used for more personal devotions. It thus has an intimate atmosphere.

2. The temple’s scale is small–the door to the central shrine is only about 4 feet high. Most travelers find its gentle size a relief from Angkor Wat’s sensationalism.

3. Banteay Srei was constructed from pink sandstone. It was relatively easy to carve, and it thus helped Khmers develop new standards of realism.

Some of the temple’s sculptures are among the most expressive in Khmer history. Above is the dual from the hallowed Ramayana, in which two monkey brothers, Valin and Sugriva, fight to the death over the throne. Their bodies are carved so deeply that they seem about to leap from the temple. The fury in their faces can make any seasoned world traveler shutter.

Banteay Srei also has the first carvings of large narrative scenes (we’ll see examples in the next post). Temples could now dramatize great epics like the Ramayana, and advance towards the glories of Angkor Wat and the Bayon.

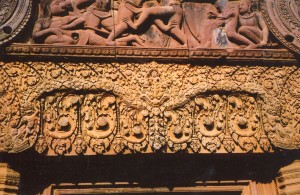

4. The pink sandstone allowed traditional Khmer forms to be carved more deeply. Above, we see the lintel form with dense foliage that earlier temples like Preah Ko had. But now its depth makes it more three dimensional.

We also saw that Khmer elites made surfaces and lines as elegant and animated as possible at Preah Ko. The builders of Banteay Srei took this love of the ornate to new heights.

And they applied their love of making every square inch ornate to the base.

So, all of Banteay Srei’s surfaces and lines glitter–they avoid the Euclidean clarity and simplicity that ancient Greeks loved so that every inch sparkles. They radiate a mixture of aristocratic elegance, intimate private devotion, and animated power that seems to infuse nature in the tropics.

Banteay Srei is one of the most ideal examples of Khmer aesthetics, so we’ll examine some of its narrative scenes in the next 2 posts, beginning with Banteay Srei.

Please note that this small temple is very popular. Rajendravarman’s armies of laborers have been replaced by tour buses. The jam packed bodies in wide-brimmed hats can detract from Banteay Srei’s intimacy. Get there as early, or stay as late as you can (the pink sandstone is sublime in the afternoon sun), screen out the crowds and linger over every detail. Banteay Srei will reward your efforts many times over.

{ 2 comments }

Henri Mouhot found it difficult to believe that the Khmers actually built the city complex, and dated it mistakenly to the time of the Romans.

He did a lot of great work, and risked his life several times while doing it. The Khmers were only being discovered when he worked, in the late 19th century. As time goes on, we learn more and more about them, and find that they were more fascinating than we had thought. I can’t wait to go back in April!

Comments on this entry are closed.