This sure doesn’t look like yesterday’s pics of Greece–where’s our hallowed classical balance?

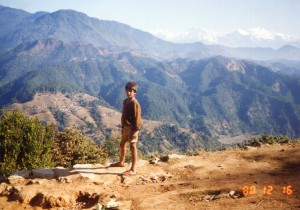

The Himalayas are so much higher than Mt. Olympus that Zeus would have frozen his gonads off. Cover up if you want to enter this post!

This is close to the kind of world that ancient composers of the Rg Veda lived in. They migrated through riverine valleys within forbidding mountain ranges in Central Asia. They and the ancient Greeks were distant cousins–they shared Indo-European roots.

The last post looked at a key concept in some of the West’s earliest literature–in Homer. Nostos (a return to one’s community and home) is basic to the Odyssey. Ulysses is stranded on the island of a temptress called Calypso, and he longs for his home and wife, Penelope. The whole narrative is about his journey back to his familiar world, and his battle to win it back from other warriors who were trying to take it. So far, so Greek.

But Indo-European roots and Indian cognates of nostos had other meanings, which suggest a different world.

Douglas Frame and Gregory Nagy write that the more ancient Indo-European verb nes meant a return to light and life, and that it was associated with the sunrise, and with returning to conscious life after death. Indians and Greeks developed conventions that treated this idea differently.

Indians were used to living in larger-than-life lands. The Indo-Europeans who migrated into India around 1700-900 BCE lived among mountains that the Nepali boy pictured above called home.

As they settled into the subcontinent, they met ancestors of dudes like these, who were living in an equally larger-than-life land of searing heat and pounding monsoons. Both cultures converged. Ancient Indians did different things with words and ideas than Greeks usually did.

The Greeks usually saw reality in terms of distinct domains, proportion and linear relationships–yesterday’s post on ancient Greece explains that the physical landscape was one of the reasons. Their environment was full of small and distinct islands, coasts and valleys, and this helped shape their thought.

So the Homeric tradition saw nostos as a return to family and community–what’s tangible and cozy. But nes had meanings that were more in terms of the larger cosmos.

Nagy notes that nes was connected with the sunrise, and possibly with ancient Indian divine twins called nasatyau, who helped bring about the sunrise. He noted that the Odyssey is also connected with the sun cycle–Odysseus’ return from the sea and from his journey to Hades were associated with the sun’s return. But this meaning is usually more implied than explicit–details of Odysseus’ adventures are described more.

Indians developed the cosmic dimensions of nes more–in yogic traditions and in the Upanisads, which stressed overcoming the whole cycle of death and return, and merging with the entire universe.

Ancient Greeks and Indians shared common roots, but both often saw the basic processes in nature differently–the former in terms of the tangible community and the latter in terms of vast domains.

Culture and nature converge in many cool ways to shape people’s assumptions about what’s most basic. Words and ideas often mean different things as they travel from one tradition to another. In each case, they reflect an infinitely rich environment that’s even more enchanting than Calypso’s island.

Comments on this entry are closed.