Indian art ain’t your father’s Romanesque or Gothic cathedral either.

Above is a carving of the Last Judgment over a portal at Reims Cathedral.

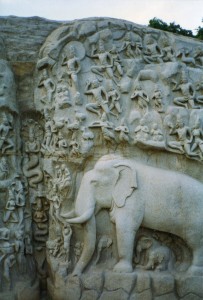

And above is Mamallapuram’s carving of the descent of the Ganges River. Both have a couple of common traits:

1. They’re of cosmic-scale events–they have important meanings for all life forms on earth and heaven–and in the first panel, a very nasty place below.

2. They’re exuberant–the guys who planned and carved these friezes enjoyed portraying as many beings as possible.

But they also reveal two different ways of seeing the world and representing reality.

Reims Cathedral’s Last Judgment portal is an excellent example of Western ways of seeing. It’s linear–the events are arranged in rows as neat as military drills. Christ is on top. The resurrection of the bodies is in the two levels beneath him. Virtues and vices are under them, and the elect and the damned are on the bottom. Around them are six saints, and above them hover three rows of beings: angels on the outermost level (the most highly evolved), deacons in the middle, and wise virgins on the inside of the left and foolish virgins on the right. Welcome to Medieval Western thought–every being is in its place in an ordered universe, with God as the creator, and Christ as the judge and redeemer.

Above, we see the deacons and wise virgins in a neat row. They could take their time to contemplate the universe in those pre-digital days.

Above we see a detail of a pillar around one of the the Basilica of St. Denis’ portals. Nature’s forms are exuberantly portrayed, but within firm lines.

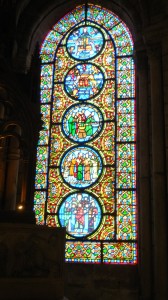

The stained glass windows at the Basilica of St. Denis also has exuberant forms hemmed into linear arrangements. The forms are so vivacious that they threaten to burst the lines, but they never do. The love of nature that French artists were expressing in Gothic cathedrals in the 13th century seems to be in a tense relationship with God’s order, as though nature wants to break free. But God’s linear order holds firm.

But the frieze at Mamallapuram isn’t divided by lines. All beings in the universe are portrayed in the same field, and the unity of life is stressed more than divisions between species.

In the story of the descent of the Ganges, we saw that Indian narratives often represent the universe as a vast and unified field, rather than one partitioned into distinct domains. The frieze at Mamallapuram visually reflects this tendency of stories to range across the universe (to use the title of a beautiful song by George Harrison). Both media (narratives and visual arts) reflect each other in India and the West, and they both reinforce their immensely rich ways of seeing the world.

Comments on this entry are closed.