Many people in China consider the columns in Qufu’s Confucian temple’s main hall (the Palace of Great Establishment) to be the most beautiful in the world.

People admired them so much that they had to be covered with red silk when Emperor Qianlong visited so he wouldn’t lose face.

What a contrast with the Parthenon’s columns in Athens. The Parthenon is generally considered to be the most beautiful building from antiquity. Let’s examine these two cultures’ most honored way of treating this basic architectural element–each reflects one of the world’s most influential world-views.

The edges of the Parthenon’s columns are uncarved and fluted. Their linear forms are thus highlighted. They’re abstract and perfect.

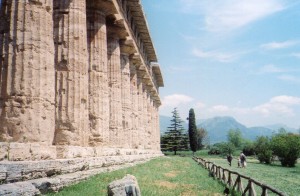

Temples all over the ancient Greek world sported these columns, which stressed the simple, abstract line. Above, you can see them holding up the temple of Neptune in Paestum, Italy.

You can also see a striking contrast between the temple and the jagged mountains beyond. Order, civic life and proportion stand out from untamed nature. The Parthenon in Athens also stands out in this way from the acropolis’ rugged cliffs.

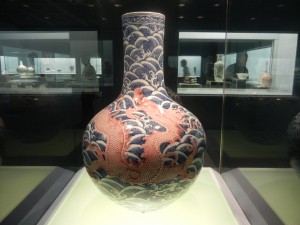

But the Confucian temple’s columns are carved from bottom to top with a pattern of two dragons playing in the clouds. The entire column seems infused with energy that flows smoothly throughout. There are no sharp distinctions or separate objects–the whole environment is integrated. This ideal became established very early in ancient Chinese thought.

Motifs of dragons and clouds convey this concept of smooth flow of energy throughout the whole very well. This concept has also been basic in ideas of yin and yang patterns, and in ancient Chinese medical theories. Since this concept of smooth flow has been more basic in Chinese thought than ideas of abstract lines, Chinese artists illustrated it in many media.

The stone slab between the steps to the Confucian temple’s main hall repeat the dragon pattern. Beijing’s Forbidden City has several of these too–the emperor didn’t need to feel ashamed about his.

Dragons in clouds and water also grace thousands of vases, cups, bowls and plates from the Ming and Qing dynasties. The perspective doesn’t focus on one point. Instead, patterns of yin and yang energies smoothly flow throughout the entire work.

Westerners and Chinese structured their thought around certain patterns, and artists produced them in many media, which were circulated throughout what people considered to be the civilized world. Folks saw these patterns several times every day as ideals of well being. People still hold these ideals because they have been reinforced millions of times over thousands of years.

These ideas became so deeply ingrained that they show up in modern art and modern architecture.

What a culture considers most basic actually reflects an infinitely rich landscape. You can see more of the Western landscape in the next post, on ancient Egptian obelisks.

Comments on this entry are closed.