One thousand years before the Shang Dyansty’s capital, Zhengzhou, was bustling, the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids and the Sphinx at Giza.

These monuments are so beautiful and magnificent that all of nature’s power, and all of the ties that order society, seem concentrated in them.

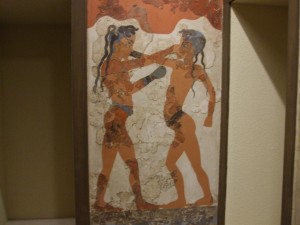

When the Shang Dynasty reigned from Zhengzhou 3,500 years ago, the Minoans on Crete and their colonies (the dudes giving each other nose jobs are from Thera) painted realistic images of people and animals. Both of these civs developed art that keeps the perspective focused on individual objects that stand out from their surroundings. The existence of the object, its basic forms and its beauty have been some of the most key ideas in Western thought ever since. It’s real cool that these ideas were emerging so long ago, and that they still shape our ideas of what truth is.

But China developed different ways of thinking and perceiving which are just as ancient and current. The Shang Dynasty did a lot to advance Chinese thought patterns. Come in and explore–nobody will punch you in the nose, but I can’t guarantee that the dragons will stay away.

Here are some more facts about the Shang Dynasty.

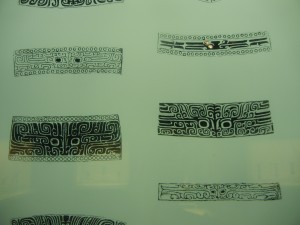

1. Decorations of Shang bronze vessels, which royals used to hold meat and wine when they sacrificed to their ancestors, were originally in a thin band around the body. This phase is known as Style I. Then lines of decorations varied in their thickness. This is Style II, and they made bronzes more dramatic–the last post on the Shang Dynasty describes this style. But then the decorations spread all over the surface.

The designs cover the surface of the above you.

2. This spreading of patterns is known as Style III.

The Shanghai Museum displayed several common patterns of early Shang bronze decoration–

Shang bronzes lack things that ancient Egypt and Greece proudly represented: people and narrative scenes. Shang artisans seem more concerned with making the vessels look energised, as though that would keep links between rulers and ancestors vital–and perhaps punctuate distinctions between classes.

The above Greek ceramic vessel was made around 700BCE. Greeks were just beginning to paint people and narrative scenes on them after emerging from their Dark Ages. Scenes later became more realistic, but a thing that beautified Greek ceramics in early and mature periods was the emphasis on abstract lines which distinguished areas on the vases. Painters partitioned ceramics into clear horizontal bands which covered the whole surface. But Chinese designs didn’t emphasize lines or abstract geometric shapes.

Patterns on Shang bronzes often flow over the whole surface.

Chinese thought has often emphasized the flow of energy through the whole system, rather than the concentration of the perspective on objects that stand out from their surroundings, and the ordering of perspectives by linear relationships.

1,000 years after the Shang Dynasty, the famous Yin/Yang pattern emerged in art. Instead of lines and permanent geometric shapes, the emphasis is on harmonious flow throughout the whole. The two spots in the middle represent some of Yin being in Yang and some of Yang being in Yin. Yang is masculine and Yin feminine. But all men have feminine sides, and all women have masculine aspects–nothing is completely distinct. All patterns intermesh in traditional Chinese thought.

David Keightley, in Heritage of China, noted that a lot of Shang designs have bilateral symmetry, as though the kings were already thinking in terms of 2 animated patterns that complement each other.

The glories of Chinese gardening and landscape painting are also based on flows of holistic energies. The above shot (from the White Horse Temple in Luoyang) is very different from the picture from Giza. At Giza, power is concentrated in a small number of objects which stand out and command your perspective. But in Chinese gardens and landscape paintings, all domains are interwoven. Though the Shang bronze patterns weren’t as refined, they helped accustom people to thinking of nature in these terms.

3. Robert Bagley, in The Cambridge History of Ancient China, wrote that bronze vessels spread from the Shang kingdom when Style III had emerged. Rulers exchanged them as gifts. States as far away as Sichuan (Sanxingdui), and the Yangtze, (Wucheng, Xin’gan and Panlongcheng) developed their own bronze-making traditions. Most places incorporated energized and flowing patterns.

Chinese architects didn’t use stone like Egyptian and Greek builders did. They made buildings from wood, bricks and rammed earth–products of the soil. Stone has been a hallmark of permanence in the West, and its use in pyramids and Greek temples has made their clear lines seem so permanent that they’re the basis of reality. When ritual bronzes circulated between states in China, they seemed like unifiers of the world and cosmos to a greater extent than they would have in the West.

As the bronzes circulated in China, they helped give the land a common culture which included a shared way of seeing the world. It was elitist–the rich made these things and used them to link their authority with the power of spirits. But it also developed into one of humanity’s most creative cultures. Traditional Chinese history has given the Shang Dynasty a bad rap–wine swilling kings oppressing the people without Confucian ethics to balance their power. But Confucianism also grew out of the sense of a holistic and harmonious society and universe.

Whether you like its kings or not, we all have to raise our wine glasses to the Shang Dynasty.

And let’s raise a huge bronze vessel to the richness of cultures around the world!

If you’re up for the flight, ancient India was equally rich–some very cool things were happening there when China’s Shang Dynasty thrived, and they shaped Indian thought up to today.

Comments on this entry are closed.