Chang’an, China’s capital city during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), was one of the greatest metropolises in the pre-industrial world.

Big Goose Pagoda (pictured above) was finished in 652 to commemorate Xuan Zang’s journey to India, and to house Buddhist scriptures. Chang’an was a crossroads of cultures from India and Central Asia to Japan. All converged there and created some of the greatest glories in China’s cultural history. But there were also lots of social tensions. There was never a dull moment in Tang Chang’an.

The founders of Chang’an tried to create a society that was controlled from the top, with the different classes living in their own quarters. But the great city attracted so many different people that the diversity and new pleasures threatened to overturn this order.

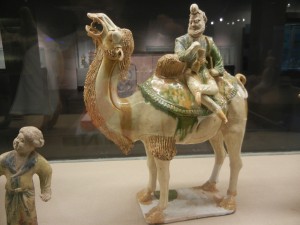

Merchants from Central Asia, with their bushy beards, hawk noses and sacks of exotic goods on the backs of camels protesting with weird groans that no other beast emits, were common sights in town. There were many other novelties.

And the rich knew how to enjoy them. Many works of Tang sculpture are known for plump faces, elaborate hair-do’s and flowing gowns. These figures populate Shaanxi museums as much as the foreign traders do. The wealthy made both for their tombs to help ensure an equally privileged afterlife. You can almost imagine the woman above pinching her nose if one of those men were to pass by her.

Aristocrats were passionate about horses. Fast Arabian breeds were their sports cars. The Chinese imported polo from Iran. The government bred horses systematically, and they were key strategic weapons in the Tang Dynasty’s political offensives. Figures like the above one abound in museums too–elites were determined to enjoy the afterlife in style.

Poetry reached new levels of sophistication. Li Po (701-762) was a dreamer, and he wrote about beautiful natural landscapes. He was an outsider–from Central Asia, and then Sichuan, and possibly from a Turkish family. His frequent references to moonlight were influenced by Turkish culture. He often got drunk–a state that Daoists identified with the spontaneity that they aspired for. But it was also considered a barbarian trait. Li Po thus represented the exotic and emotionally immediate.

Tu Fu (712-770) was born near Chang’an, and was more sober. He had to be. He failed the imperial examinations that would have a gateway to a successful career and the pleasures of elite life. Tu Fu had to struggle to live, and his family sometimes starved–so badly that one of his children died. His poetry is known for compassion. The Tang Dynasty was wrenched by a military rebellion in 755-63 that it never fully recovered from. Tu Fu’s humanity resonated with all too many people who either lost their Arabian horses and elegant clothes, or aspired for them and failed.

Both poets conveyed the full range of human experience as the Tang Dynasty waxed and waned. But we’ve only looked at the pleasures of the upper classes and the disillusionment of those who couldn’t live so well. In the final post on the Tang Dynasty, we’ll meet a broader range of people who made Chang’an bustle. We’ll peer into their daily lives and see what made the capital so exciting.

Comments on this entry are closed.