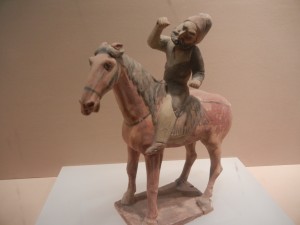

I had read about guys like this in books on Chinese art, but I was surprised that there were so many of them.

They were made during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Trade grew along the Silk Road in the early Tang, and through southeastern port cities (especially in the later Tang). Merchants, political envoys, Buddhist pilgrims and vagabonds from Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Korea and Japan went to China to live, and the Tang became the most cosmopolitan dynasty in China’s history. But this guy on the horse isn’t portrayed in a very dignified way. Why is he so animated without any SUV drivers to yell at? His sub-Mandarin bearing suggests mixed feelings about the new diversity.

The capital city, Chang’an, had China’s highest concentration of foreigners. Merchants brought furs, exotic animals, rare plants, tropical wood, perfume, drugs, exotic food, textiles, jewels, metals and slaves from all over the known world.

But Chang’an didn’t start out that way. In the late 6th century, the new Sui Dynasty had unified China for the first time since the Eastern Han Dynasty fell in 220. Many kingdoms had been battling each other, and the new emperor built a new capital there to signify order. It was laid out in the cardinal directions, and each wall stretched for over 5 miles. The imperial city presided in the northern central part. The elites lived in the northeast. Commoners lived in the west, and to some extent, the south. There was an east market and a west market. All domains were in order.

And the emperor imposed more order. 12 main east-west and 9 main north-south roads divided Chang’an into wards. The number 3 corresponded to the 3 powers in nature: Heaven, Earth and Man. 9 represented the 9 provinces of the legendary Emperor Da Yu, and 12 corresponded to the 12 months. The city was thus harmonized with the whole universe.

The wards were walled, and people living in them were under curfew. Drums in towers (like the one in the second photo in this post) were pounded when the gates opened in the mornings and closed in the evenings. The wealthier enjoyed more freedom and luxury, like the home in the above picture.

But like the growing towns in medieval Europe, this order imposed from the top created tensions that would threaten it. More and more diverse people (like the bloke in the first photo) and customs were becoming common features of the capital. Dynamics between them and the imperial order would make Chang’an arguably the world’s most exciting city then. We’ll explore it in the next post on Tang China–including its elegance and dirt.

Comments on this entry are closed.