A teacher that I had in a class on Homer’s Iliad said that the ancient Greek gods, in their frequent quarrels, were a typical Mediterranean family: “Dishes flying”.

A student with Greek blood chuckled and said, “It’s true!” Maybe not exactly–I’ve experienced much more warmth and hospitality from Greek families than fireworks. But I do agree that ancient Greeks were unusual in their degree of seeing gods in terms that reflected worldly life.

About 1,000 years after the great Homeric texts were written, St. Augustine of Hippo wondered how anyone could have worshipped such contentious, lecherous, wine-swilling creatures. But Augustine was from a different time. Here, we’ll have a quick look at a glorious vision from the early Western tradition, which still shapes our thought.

Homer’s Iliad begins with a display of male dumbness: the greatest Greek warrior, Achilles, and the Greek army’s leader, Agamemnon, argue because the latter took the former’s war booty–a woman named Briseis. Achilles deserts his comrades in a huff, and the war with the Trojans drags on and on, taking many lives from both sides.

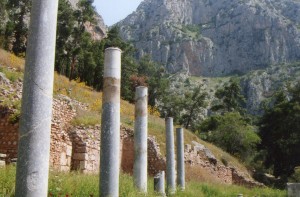

But from this ignoble beginning, the Iliad’s Book I expressed one of the most influential and beautiful ways of seeing reality that any culture has devised. The above pic gives us a hint. Delphi’s forbidding slopes are translated into ratio.

Though Pergamom’s Temple of Trajan was built by Romans 600-800 years after the Iliad was written, it too follows the classical tradition of portraying sacredness in terms of balance, ratio and clarity.

So does the Iliad’s Book I. It ends in a godly row! Zeus and his wife, Hera, are going at at. No need to throw dishes–they’re gods, and thus fearsome enough when they yell. Zeus proves it when he threatens to lay his hands, which no warrior ever stood against, on her.

Hera’s son, Hephaistos, a crippled blacksmith, comforts her with a goblet of nectar. He then pours drinks for the other Olympians. They laugh uproariously at his limp, feast throughout the day, and savor Apollo’s lyre playing.

In one of the West’s earliest texts, we can already see several of Western thought’s most salient features:

1. Concepts of divinity that reflect human life–the heavens conceived in terms of this world. Greek ideas of the godly row were probably inspired by Mesopotamian myths about Marduk having to win his position by battling, and by the other Indo-European civs in modern Turkey and Syria. But the details–the feast, the drinking, the laughing, the music–were Greek. The Athenians made the above horse from the Parthenon so realistic that you’d expect to feel its breath’s heat.

2. A love of balance and ratio–a human fight and a divine fight bracket both ends of the Iliad’s Book I.

3. A sense of glory in the physical world. What St. Augustine found revolting, the German philosopher Nietzsche found enthralling when he was a young classics professor writing The Birth of Tragedy. He admired the Greeks of Homer’s time for their full vision of life–their ability to affirm the world and enjoy things intensely, and their willingness to look directly at the most horrific human behavior without flinching. He felt that folks in late antiquity were lily-livered.

What I find enthralling is, many of the foundational ideas in Western culture were expressed so well in its early stages. Greeks were very Greek from the beginning. Most Westerners still are.

We’ll compare this veiw with ideas of gods from ancient India in the next post, and see that ancient Indians were already very Indian.

Comments on this entry are closed.