In the late 8th century BCE, Greek ceramics already expressed Western ways of seeing reality.

It’s different from art and perceptions which had developed in China.

All the scenes on the Chinese vase flow together within a single unified field. But the figures on the Greek vase are distinct, and abstract lines dominate the surface. How did these 2 views of the world emerge?

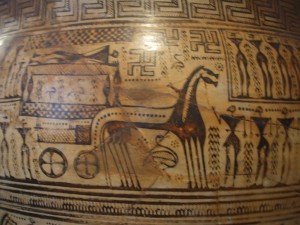

Here are some characteristics of many early Greek ceramics:

1. Jeffrey M. Hurwit, in The Art and Culture of Early Greece, 1100-480 B.C., noted that Ancient Greece’s early ceramics were often schematic–makers, like the Dipylon Master, conceived the human body as pieces, rather than as one organism.

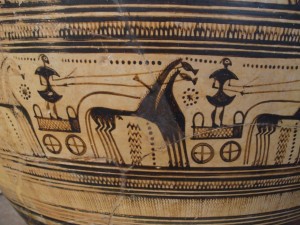

In both of the above Greek vases, the human body is a mixture of parts which have different forms. Some forms are abstract shapes, like the triangular torsos in the top shot, and the armor of the 2 chariot drivers above, which look like pinched circles.

2. Bodies in all the above Greek vases are distinct units. They don’t blend into a larger flow of energy, like a lot of Chinese scenes do. Each stands out as surely as an ancient Greek temple. Entities are distinct, and their components are distinct. Everything is clearly perceivable and definable.

3. Scenes are defined by solid boundaries, which are straight lines abstracted from the scenes.

In the above bowl, bodies stand as distinct units, and all are bordered by abstract lines.

The same type of schematic graces the above bowl.

This is a different world than the one which China’s Shang Dynasty’s bronzes embodied, where animated energies and animal motifs flowed throughout a unified field. As Greek culture was emerging, creating common art forms and becoming conscious of itself, its people liked to comprehend things individually. They liked to do so on the basis of abstract forms and clear edges, within clearly delineated fields. Why?

There wasn’t one reason. Several things converged, and this has made this way of seeing reality so deeply ingrained that it seemed self evident to many Westerners for the next 2,700 years:

1. Politics being centered on the distinct city state.

2. Ancient Greece’s geography of coastlines and colonies.

3. The Agora as the center of ancient Greek civic life.

4. The ancient Greek temple’s colonnaded form as the model of enduring truth.

All these shaped people’s perceptions and ideas of what beauty and truth are. They paved the road to Pythagoreans’ and Plato’s ideas of divine geometric forms and ratios, which some modern scientists still revere.

So those simple abstract lines and shapes have infinite depth beneath their surfaces.

So do other cultures’ ideas of geometry. You can voyage to the Middle East and check out Islamic ideas of geometry.

Comments on this entry are closed.